Lazily Pulling Container Images with Podman and SOCI Snapshotter

We’re excited to announce a podman performance improvement that makes pulling container images about ten times faster on BuildBuddy’s hosted execution service, lowering customer build and test times and improving our ability to autoscale the BuildBuddy executor pool. Read on for the nitty-gritty details.

Containerization

At BuildBuddy, we use containers to isolate actions and support arbitrary code execution on our hosted remote execution service. In production we use Podman as our default container runtime, but we support Docker and Firecracker as well. One significant challenge we encounter with our container setup is that pulling a container image after cold start can be quite slow. Our executor images are about one gigabyte and it typically takes about 30 seconds to pull and extract them in our GCP production environment. Some client-provided images tip the scales at over 10GB and can take minutes to pull and extract.

Not only does significant image pull latency directly slow down customer builds and tests, it also limits our ability to autoscale the executor pool and respond to heavy load. When new BuildBuddy executors start up, they pull container images as needed. This means the first action using an image that runs on an executor incurs the latency of pulling that image and blocks other queued actions using the same image. So the faster we can pull container images the faster we can spin up new executors and start running customer-submitted actions. We could address this problem by always running more executors, or preemptively scaling the executor pool during peak hours, but at best these tricks only partially solve this problem and have other drawbacks.

Lazy image distribution provides a more promising solution. The premise is that most parts of a container image are unnecessary for most container runs, so instead of eagerly fetching the entire image upfront, pieces of the image’s layers can be retrieved by the container runtime as needed. The stargz-snapshotter implements a lazy image fetcher based on the eStargz custom image format, and the soci-snapshotter provides one based on the OCI specification for those who can’t or don’t want to convert images to a new format to support lazy distribution.

SOCI Snapshotter

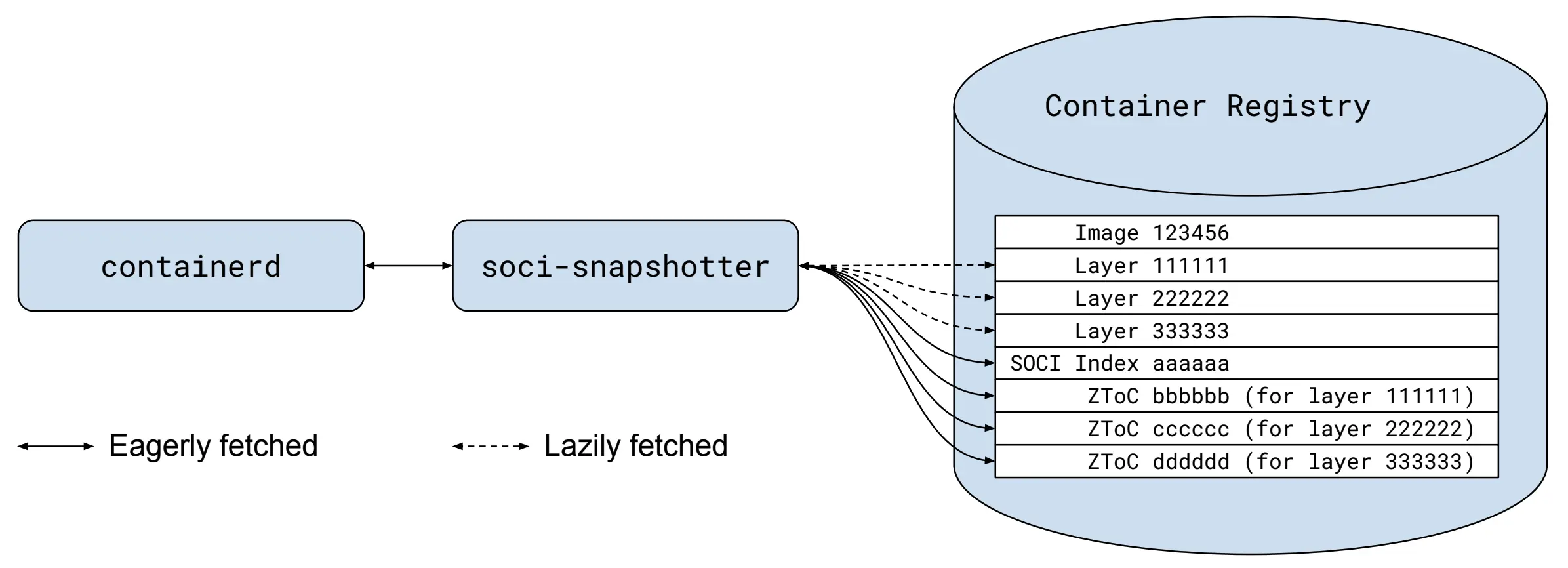

The SOCI Snapshotter acts as a local container layer store that containerd can use to retrieve image layers in place of the remote registry. Lazily fetched images must be indexed, which involves creating a zip table of contents (ZToC) indexing the contents of each container image layer, and bundling these ZToCs in a json file called the "SOCI Index" that associates ZToCs with the layers they index. Given an image, the soci create tool takes care of creating all of these artifacts. Once these ZToCs and the SOCI Index are created, most snapshotter users will push these artifacts to the remote container registry where they’re associated with the container image using either the referrers API or a fallback mechanism involving tags. Then, other SOCI Snapshotter instances can retrieve the SOCI Index and ZToCs and use those to determine where container fileystem locations exist in each layer's targz file and fetch only parts of the layer files as needed.

A typical soci-snapshotter setup. SOCI artifacts are stored in and retrieved from the container registry and used to lazily pull parts of the image as needed.

A typical soci-snapshotter setup. SOCI artifacts are stored in and retrieved from the container registry and used to lazily pull parts of the image as needed.

BuildBuddy + SOCI Snapshotter

We have a couple of caveats that prevent us from using the SOCI Snapshotter with BuildBuddy executors out-of-the-box. First, we'd like to continue to use Podman as our default container runtime, and second, we want to support lazy image distribution for container images in read-only registries -- requiring our customers to either give us write access to their container registries or add an additional image indexing step to their image deployments is a nonstarter for us.

We solved the first problem by porting the Podman support in the stargz-snapshotter to the soci-snapshotter. This involved creating a new binary in the SOCI Snapshotter, the soci-store, and hooking that up to run the store/fs.go filesystem implementation.

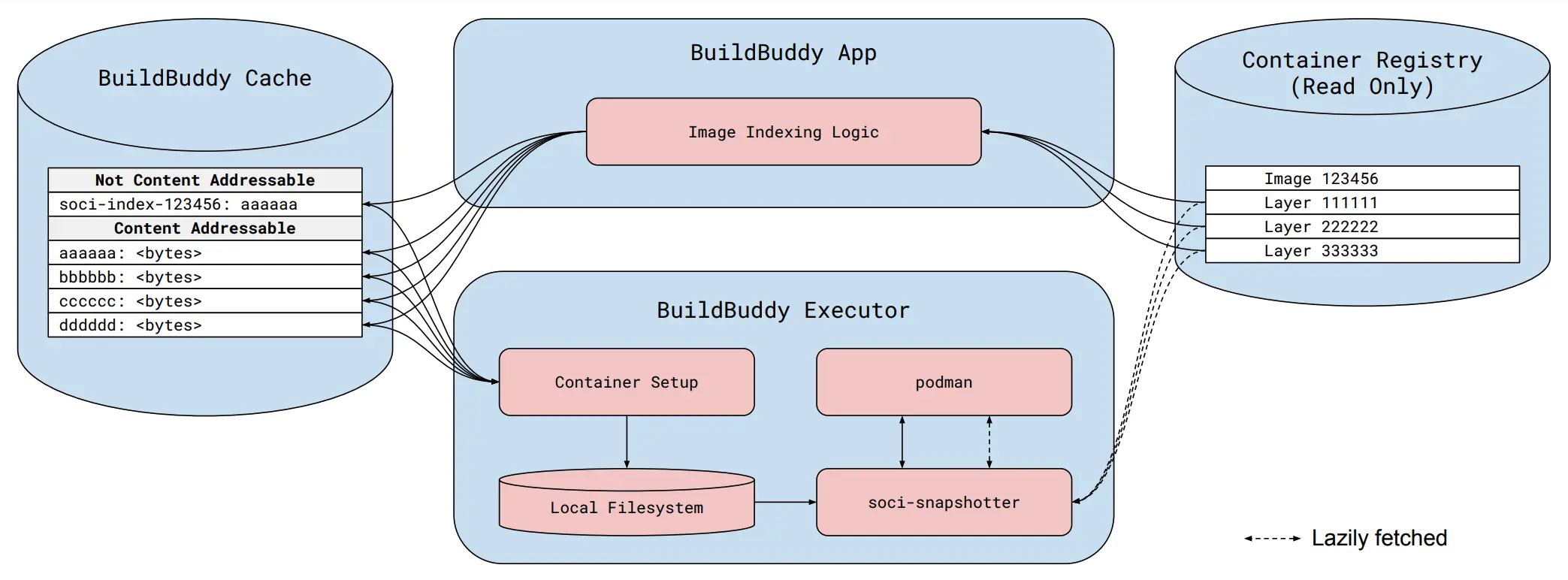

The second problem posed a little bit more of a challenge. We needed a different mechanism for storing the SOCI Index, ZToCs, and the association between a container image and its SOCI Index. Fortunately for us, the SOCI artifacts (Index and ZToCs) are content-addressable and we know how to store content-addressable blobs! The final piece, the association between the image and its SOCI Index, isn’t content-addressable, it’s just a string-to-string mapping. But the BuildBuddy cache also supports storing non-content-addressable contents keyed by a hash. So we store the image-to-index mapping by salting and hashing the image identifier, to support versioning, and adding a cache entry under that key with a value containing the digest of the SOCI Index, which is retrievable from the content-addressable store.

To support all of these modifications, we added a bit of logic to the snapshotter that attempts to retrieve artifacts from the local filesystem before the remote registry and supports reading the image-to-index mapping from the local filesystem under a special directory, again keyed by the image identifier. Finally, we set up the app and executor to look for all of these artifacts in the cache, generate them if they’re not present, and store them on the local filesystem so the snapshotter can do its thing.

The modified soci-snapshotter is available at github.com/buildbuddy-io/soci-snapshotter.

The BuildBuddy + soci-snapshotter setup. SOCI artifacts are generated on-demand in the App, stored in the cache, and retrieved by the Executor as needed.

The BuildBuddy + soci-snapshotter setup. SOCI artifacts are generated on-demand in the App, stored in the cache, and retrieved by the Executor as needed.

Authorization

Many of our customer’s container images are password protected in the container registry. We share user-provided registry credentials between the executors and the soci-snapshotter so the snapshotter can fetch registry artifacts as needed, but these credentials expire after a short time period. The setup described here doesn’t permit any unauthorized access to container images or their derived artifacts. The SOCI artifacts are only generated and retrieved for authorized image pull operations, just like standard podman pull requests.

Cache Eviction

We continuously evict the oldest unused artifacts from the BuildBuddy caches to make room for fresh data, and SOCI artifacts are no exception to this. Fortunately, the average last-access-time (including reads) of evicted items for most customers is old enough that only artifacts for rarely pulled container images are affected. Container images used regularly in remote execution or CI only require re-indexing except after being updated in the container registry.

Bugs!

After initially rolling out lazy image distribution to our executors, we saw intermittent build and test failures due to Input/output errors running binaries inside of containers. We tracked this down to a bug in the containerd docker authorization library that caused it to re-use expired authentication tokens a bit too eagerly. Fortunately, there was a pretty straightforward workaround while we wait for an upstream fix.

We also observed occasional panics in the soci-store running in our development and production setups. To gather more data, we ran a version compiled with the go race detector in our development environment for a few weeks and tracked down two sources of these panics. First, we observed unprotected multithreaded access to data cached in in-memory inodes which was easily fixed by protecting those accesses with a mutex, a change that we pushed upstream. We noticed this issue before the upstream maintainers because we concurrently pull two container images on executor startup, sometimes within less than a millisecond, a behavior that exacerbates latent multithreading bugs like this. And second, both the soci-store and the SOCI Snapshotter were affected by a bug in the go-fuse library that caused them to return incorrect values for some Lseek calls. This lead to out-of-bounds reads of soci-store in-memory files, and panics. This was easily fixed by upgrading the soci-store's go-fuse dependency past github.com/hanwen/go-fuse/pull/488 which fixed the bug. Interestingly, this bug manifested slightly differently in the SOCI Snapshotter, but thankfully the same solution addressed both symptoms. Both of these bugs occurred pretty infrequently and were difficult to reproduce, so we were thankful for the additional information from the go race detector.

Finally, we encountered issues caused by private container registry credentials expiring mid-run. We were able to fix these problems by hooking up the background layer fetcher in the SOCI Snapshotter with the newly introduced soci-store binary, reducing the likelihood that a container layer part will be requested after the supplied credentials have expired.

Performance

We've been using the lazy image distribution mechanism described here in our development environment for a few months and have observed an almost tenfold decrease in image pull latency after cold start, from about 30 seconds to about 4 seconds for our executor images in the common case where the SOCI artifacts are available in the cache. In the rare case where the SOCI artifacts are unavailable, container image setup is about 10% slower due to the need to pull the image, index it, and fetch the SOCI artifacts from the executor. After testing this setup in dev, we rolled it out to all BuildBuddy cloud customers in two phases. Earlier this summer we enabled lazy image distribution for all publicly pullable container images and this month we enabled it for images stored in private container image registries. We've observed the same almost tenfold decrease in image pull latency for customer images with no action required by our customers.

Because lazy image distribution defers layer fetching from pull-time to run-time, it's expected that some container run operations are slightly slower -- specifically, when part of a layer is needed but not available locally, it must be fetched from the remote registry at run-time. Fortunately, our container operation throughput is high enough that this performance penalty isn't noticeable in our environment.

We’re excited about the promise of lazily fetching remote resources in more circumstances and hope to build on what we've learned from this project to continue to improve the BuildBuddy remote-execution platform.

If you want to learn more about BuildBuddy’s remote execution service or any of the other features we offer, or give them a try, check out our documentation. And if this sort of engineering challenge sounds interesting, we’re hiring!